Creekstone Press Publications

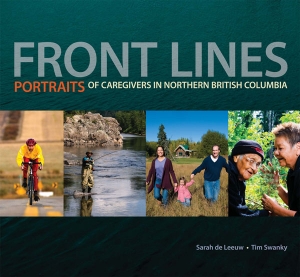

Excerpts from Front Lines: Portraits of Caregivers in Northern British Columbia

When I was 12, I almost died.

Southwesterly, gale-force winds were slamming into Haida Gwaii on the night it happened. Like every other night of the year, there was no surgeon on the islands when my appendix ruptured.

The on-call doctor at the Queen Charlotte City clinic, though, was a generous man who listened carefully when my parents explained I didn’t seem able to move and was vomiting profusely. Despite the horizontal rain, he paid us a house visit.

I remember he carried a big, beat-up, black leather bag that opened like a yawn. Even as the pale-blue walls of my bedroom swam around me, I focused on how wonderfully old-fashioned, and somehow comforting, that bag seemed.

What happened next remains a blur. I remember being loaded into an ambulance that almost couldn’t make it to our house because we lived on a cliff with a steep, rutted-out track as a driveway. I remember hearing the groans of ropes and the bashing of metal against concrete as the sole ferry that crossed between Graham and Moresby islands, carrying two first responders, my mother and me, docked and then strained against the swollen ocean. I remember waiting on the tarmac of the Sandspit airport as radios crackled with messages urging a circling Learjet from Vancouver to land despite the storm conditions. I remember how a gust of wind almost snatched my stretcher away from the half-dozen people trying to load me onto the plane. And, I remember a feeling of weightlessness, of cold rain biting into my face, and of knowing without a shadow of doubt that everything about the North was bigger than I was.

I am aware almost every day that without that heroic group of people, I wouldn’t be alive. I’m also aware that a very particular geography – the remote, northern archipelago of Haida Gwaii – exacted a special kind of health care that night in which people took certain risks and went multiple extra miles.

Northern British Columbia, and the people who live here, are sometimes maligned. Towns are described by guidebooks as places “not to linger in.” People who live here disagree. In story after story people with responsibility for caring for their fellow human beings express gratitude to the North. This might seem like an abstract idea: being thankful to a place, a location. The more people tell stories about connection with place, though, the clearer – and less abstract – the idea becomes.

Linger a few moments in the shadows of the Seven Sisters, the Northern Rockies, and the Coastal Mountain Range. Stand for a few minutes on the banks of the Skeena River during eulachon season when the waters seem to run silver and hundreds of bald eagles hover everywhere you look. Spend an evening in a café in Fort St. John run by two brothers who moved up from Vancouver specifically to offer home cooked meals made with as many local ingredients as possible. Walk into one of our bookstores or canoe Stuart Lake. Each of these places, and thousands more, elicit simultaneous feelings of humility and privilege. The very place of northern BC, person after person told me, allowed them to live and work in ways that would have been impossible anywhere else.

From walking on estuaries to partaking in community theater, from sailing into tiny ocean inlets to buying local art from tucked-away galleries, and from gardening in the last light of long summer days to organizing competitive marathons across scree slopes in mountain passes, it seemed the people committed to being caregivers in the North felt cared for and inspired by the physical geography.

Place and land as critical to health was never an abstract thought for Sophie Thomas. A Dekelh Elder and healer from Sai’kuz, Sophie passed away at the age of 97, just a few short months after she and her daughter were photographed for this book. The almost century-long relationship Sophie had with her family’s Keyoes (family territories) and other vast lands in the northern interior resulted in The Plants and Medicines of Sophie Thomas, a book now in its third printing. All aspects of health, according to Sophie, were linked to land. The absence of her voice belies the strength of her presence, both in the pages of Front Lines and across the region. Many people who partook in this book knew Sophie. More knew of her. Some were related to her, a lineage that inspired great pride. Even though I did not know her, I felt myself missing her.

Indigenous peoples were the first people in this now mapped, surveyed, and bordered land of northern British Columbia. It is no surprise, then, that Indigenous health care practitioners – be they nurses, social workers, surgeons, or dispensing opticians – talk about healthiness as connected to equality. And it is no surprise that many non-Indigenous caregivers talk about trying to provide health care in northern British Columbia that will address inequality. Sophie Thomas’ daughter Ruby told me recently her mother had dedicated an entire life to educating people, to spreading the message that people’s well-being could not be separated from the well-being of the earth. That seems to be at the heart of most people’s stories about their lives and providing health care in northern BC.

It’s not easy to write about people who have dedicated themselves to providing health care in what remain landscapes on the margins. There’s a risk of romanticization, a risk of turning real people into caricatures of some euphoric, pioneering, stoic archetype whose work is always valorous. The people in Front Lines would be the first to articulate their frailties and fallibilities. According to most, however, knowing those traits, and having them reinforced by the sheer magnitude of the geography that surrounds us, reinforced the need to care for people in deeply empathetic ways. We are, even and especially as we as care for each other and tell each other our stories, small in and always impacted by this land. Which, as the life and legacy of Sophie Thomas makes clear, is something to be celebrated.

Sarah de Leeuw, January 2011

Back to Front Lines: Portraits of Caregivers in Northern British Columbia